The CMHC’s annual Northern Housing Report paints a bleak picture of the housing market in Canada’s northern territories, where a high percentage of residents lack suitable, adequate and affordable housing.

No need to rack one’s brain for a salacious headline, the housing situation of many Indigenous Peoples in Canada is a nightmare that has been unfolding over the last century: mould-infested dwellings, uninsulated shacks, unreliable electricity and a lack of drinking water—in a country with access to 20% of the planet’s freshwater resources—are evident symptoms of a persistent housing crisis plaguing First Nations, Métis and Inuit populations.

“It’s like we have to be beggars in our own land,” said Conrad Ritchie, a band councillor with the Saugeen First Nation, in a Guardian article that spotlights the plight of residents in Cat Lake, an isolated reserve in Northern Ontario. The community, home to roughly 700 people, had to declare a state of emergency over dangerously poor housing conditions, and more than 90 of its homes have been condemned due to concerns over black mould. Photos of the village resemble a post-apocalyptic world: residents living in dilapidated dwellings, fending off mould in lieu of hordes of zombies.

This is far from an isolated case, there are many “Cat Lakes” in Canada: communities such as Neskantaga First Nation have had a boil-water advisory for the past 25 years, while in Nunavut, in 2015, the tuberculosis infection rate among Inuit was 26 times the national average, thanks in part to overcrowded housing.

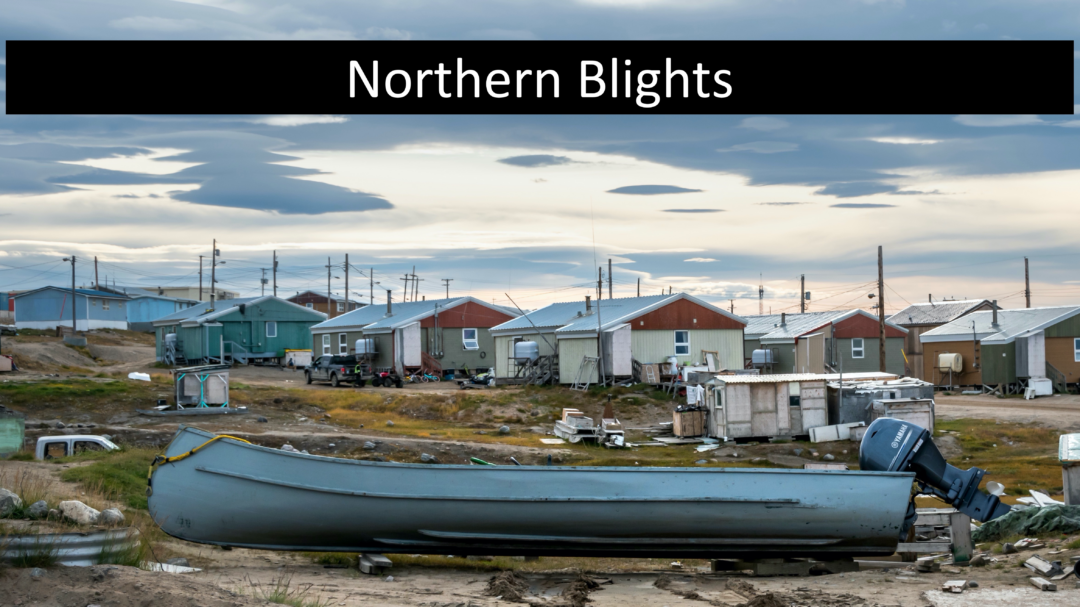

In Canada’s northern territories, housing shortages, inconsistent housing quality, culturally inappropriate homes, a lack of community housing and high construction and maintenance costs worsen the situation, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s annual Northern Housing Report.

The 2020 report, focusing on housing-market conditions across the three major centres in the territories (Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit), reveals affordability challenges are among the most pressing issues facing the North.

Particular challenges

Much of the housing in the North is provided through territorial housing providers—such as the Yukon Housing Corporation, Northwest Territories Housing Corporation and Nunavut Housing Corporation.

Not surprisingly, there are huge gaps in the housing continuum in all three cities, resulting in exorbitant housing costs: in Iqaluit, an average two-bedroom rental goes for $2,736 a month, or $33,000 a year.

Some highlights from the Northern Housing Report:

WHITEHORSE: With Yukon having the oldest population in Canada’s three territories, its demographic growth has largely been supported by migration flows—which have been stalled by Covid-19. Market affordability is certainly out of reach for many. An estimated 18% of all households in Whitehorse in 2018 were unable to secure market housing without assistance. The average rent for a 2-bedroom apartment is $1,227, while 12.7% of households are in core housing need.

“A household in core housing need is one whose dwelling is considered unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable and whose income levels are such that they could not afford alternative suitable and adequate housing in their community.”

— Statistics Canada

Other observations in the report include:

- In Whitehorse, a growing elderly population and a slowdown in international migration has decreased rental demand;

- Low resale inventory and a persistent sellers’ market have supported price increases across many housing forms;

- In the new-home market, affordability challenges have supported a shift toward lower-price options in the multi-family segment.

YELLOWKNIFE: The Northwest Territories has a population of 44,826, about 47% of it located in Yellowknife, with two thirds of the population aged 25 and over. Employment has declined since the beginning of the pandemic, weaker economic growth will encourage more workers to leave the territory, and there is concern about a smaller working-age population supporting the costs that come with an increasingly elderly population. The average rent for a 2-bedroom apartment here is $1,744, while 10.6% of households are in core housing need.

Other observations:

- Improvement in employment among young adults and affordability challenges in the homeownership market resulted in increased demand for rental units.

- Home prices declined as fewer people move north and the growth in the senior population has slowed demand for existing homes.

- A decrease in the population of young adults (first-time home buyers), high costs of construction and land availability issues resulted in fewer housing starts.

IQALUIT, NUNAVUT: With a population of roughly 39,000, Nunavut has a relatively young populace, boasting a median age of 26.2 years, i.e., nearly half are under 25. The economy of Nunavut is primarily resource-based, with a large mining sector. As elsewhere in the North, the territory is dependent on natural resource prices and faces challenges in workforce education and retention, all of which affect its long-term economic prospects.

In Iqaluit, “land availability issues and labour shortages continue to be a challenge in creating new housing developments throughout the region,” the report notes. The average rent for a 2-bedroom apartment is $2,736, while 18.1% of households are in core housing need.

Other observations:

- A growing population in Nunavut is contributing to housing demand across the territory; however, supports are needed to ensure the availability of both public housing and market-housing units;

- Rental demand remains strong, with vacancy rates near zero for market rental units as well as social and affordable housing.

What now?

“The CMHC’s report provides a bird’s-eye view of the housing market in Canada’s North, which is a start,” says Stéphan Corriveau, executive director of the Community Housing Transformation Centre. “We can look at the findings and identify opportunities where we, the community housing sector, can intervene.

“However,” he adds, “it is time to let Indigenous housing providers lead the way and figure out how to do things on their own terms, that are culturally appropriate, and specifically curated to the realities of the northern territories.”

The Canadian Housing and Renewal Association’s Indigenous Caucus launched a campaign in October doing just that. For Indigenous by Indigenous (FIBI) is a call to action for a comprehensive urban, rural and northern Indigenous housing strategy “to eliminate the very large gap in core housing need facing Indigenous peoples in Canada’s north”—and they have a very clear vision of what that would look like:

“Funding levels need to reflect the higher construction and transportation costs and very few economies of scale. In addition, any strategy needs to include the high percentage of Indigenous people who are homeless and provide ongoing federal commitment to provide self-governing First Nations with much-needed housing funds,” reads a strategy proposal to the government included on a CHRA Indigenous Caucus website created to promote FIBI.

Although the 30-page proposal might seem ambitious, it has broad support: the CHRA Indigenous Caucus recently released a public opinion poll conducted by Abacus Data on the beliefs Canadians hold on Indigenous housing, and the results were encouraging: over 60% of those surveyed would support a national strategy focused on the state of housing for Indigenous Peoples living in urban and rural settings.

In an article addressing the results, Margaret Pfoh, CEO of the Aboriginal Housing Management Association in B.C. and a member of the Centre’s board, says, “the data prove that a majority of Canadians are acknowledging the painful reality for Indigenous Peoples. It’s long overdue that the government expands its moral concern and take action. It’s time for the Canadian government to create structural changes and dismantle the colonial practices that debilitate Indigenous Peoples [and keep them] from accessing housing.”

Until then, our eyes are turned North.

This article is the first of a series exploring the challenges in accessing and delivering affordable housing in Canada’s northern territories.