The Jean Tweed Centre has partnered with Street Haven at the Crossroads to empower women to take charge of their rehabilitation process and to support them at every step of their healing journey.

Over the years, changing perspectives on addiction and homelessness have influenced treatment and prevention, with frontline workers and people with lived experience informing and often leading the work. Although harm reduction—popularized in the mid-1980s as a solution to the health problem of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis among injecting drug users—remains controversial in some quarters, it made its way into the philosophy of rehabilitation centres and non-profits working with people struggling with substance abuse and/or homelessness.

“Harm reduction ‘meets people where they are’ with empathy, acceptance, and compassion in a non-presumptive, collaborative spirit,” writes Andrew Tatarsky in Psychology Today. Having worked as a psychologist in the field of substance use treatment for 35 years, he says it is time for a shift in thinking.

“Thinking of addiction as a disease is largely responsible for our failure to effectively treat it,” says Tatarsky. “The disease model presumes that addiction is primarily a biomedical phenomenon, a permanent condition that is arrested only by complete and total abstinence from all mood-altering substances.”

The dangers of this type of thinking? That abstinence —the complete avoidance of drugs and alcohol—becomes the only measure of success.

Busy surviving

Naturally, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to addiction. The ability to adopt “best practices” takes time and resources—something most non-profits simply do not have.

“In the community-housing sector, groups are often so busy just surviving, they don’t have time to pause and reflect, to ask themselves, ‘How can we change, how can we adapt, how can we align with best practices?’ ” says Chrissy Diavatopoulos, program manager at the Community Housing Transformation Centre. But “this is exactly what the Jean Tweed Centre is doing.”

The Jean Tweed Centre is a community agency dealing with substance abuse, mental health and problem gambling. It operates Palmerston House, a transitional housing residence, and offers supportive services to women, some with infants, battling addiction.

Realizing its attitude toward addiction was outdated, the Jean Tweed Centre partnered with Street Haven at the Crossroads, an organization housing and offering supportive services to women at risk of homelessness. Moving away from the traditional abstinence model, seen as punitive or outdated by some, the Toronto-based organizations are going a step further by involving their tenants—women who have experience living in transitional, supportive housing, and dealing with substance abuse problems.

And this is precisely what makes the Women’s Supportive Housing Engagement Project unique according to Volletta Peters, housing director at the Jean Tweed Centre. “It is this intentional creation of a seat at the table for women to meaningfully participate as co-contributors in a project that will impact their lives and the lives of other women seeking housing.”

Rich reservoir of knowledge

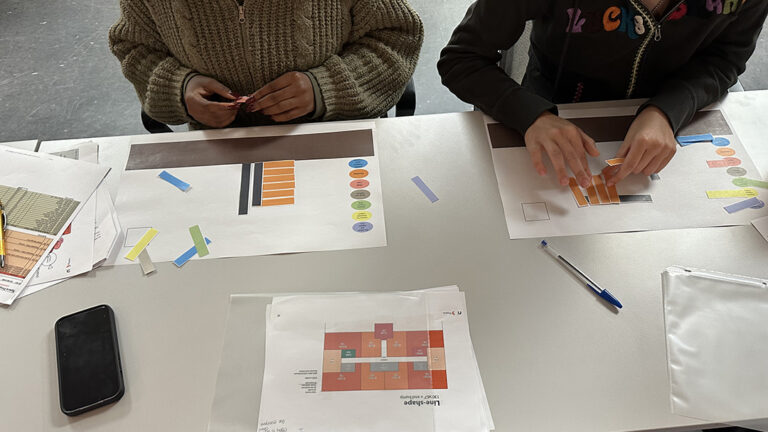

Aided by a $45,000 grant from the Centre, the project is a grassroots research and tenant-engagement initiative. Several of the 66 women living in the Jean Tweed and Street Haven facilities will learn the needed skills to research, influence, and design programs.

“The women bring a rich reservoir of knowledge and experience that helps to inform and shape all aspects of the research, including the design, implementation and dissemination of the results,” explains Peters.

Instead of a rigid structure, there will be a focus on empowering women to take charge of their rehabilitation process. Grassroot researchers with lived experience of homelessness will work closely with current residents who are members of a Research Advisory Committee to conduct a needs-assessment and program review of the Palmerston House and Street Haven housing models. They will then share their findings in an opportunity to influence housing decisions that affect them.

And for women such as Amy Wright, it provides the perfect opportunity to turn lemons into lemonade.

“I have almost 10 years of experience living in transitional and recovery housing,” says Wright. “I have had positive and negative experiences, but this project turns all those experiences into something that can be used to help women looking for supportive housing or transitional housing.”

Although much of the focus will be on a change in perspective when helping the women, the actual design of the supportive housing, and how it helps—or hinders— recovery will also be examined. “I have learned through this project that there are people out there who truly care and believe that if you use substances it does not mean you should be homeless,” Wright adds.

To learn more about the awarded project see here.