The discrimination and housing challenges faced by Black communities are illustrated by both compelling personal stories and alarming statistical data. The systemic discrimination and racism of some landlords, real estate agents and neighbors have created significant barriers – with the repercussions being felt from generation to generation. Inequalities experienced by Black people translate into higher rents, precarious living conditions, and frequent relocation, all of which affect the stability and quality of life of many families.

Organizations run by and for Black people are working to change this situation and develop more housing across the country but their modest numbers and resources are limited. The Centre supports many of these organizations through programs designed to accelerate their growth.

Among these organizations, the Black community housing society (BCHS) has made remarkable strides in Quebec over the past year. Created to respond directly to issues of discrimination and racism related to access to housing for people from Black communities, BCHS is dedicated to developing and managing affordable housing projects. It has recently launched its first project to build 230 units. We caught up with Neil Armand, General Manager of BCHS who shared his organization’s journey and challenges with us, challenges that are only becoming more acute.

What do the statistics on housing for Black communities reflect?

Discussing the issue of inequality in the context of housing, Armand emphasizes the importance of basing discussion on measurable statistics to encourage real dialogue, stressing that this is a fundamental issue that requires social action. In his view, North American and European societies are reluctant to question themselves.

“People find it hard to accept their share of the blame for injustices they haven’t personally committed, which creates a situation where it’s difficult to have genuine conversations. Today, the only way to foster authentic dialogue is to start with measurable statistics and figures. This approach makes it easier to have real, constructive conversations about persistent inequalities,” he says.

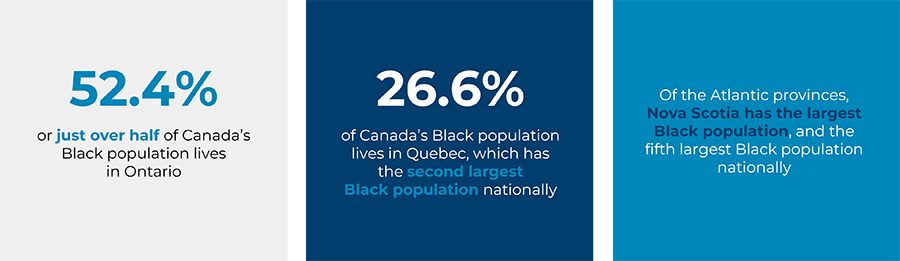

According to Statistics Canada‘s study on the diversity of the Black population in Canada, the vast majority live in large urban centres. Ontario still accounts for just over half (52.4%) of Canada’s Black population. Quebec has the country’s second-largest Black population, representing 26.6%, and Nova Scotia has the largest Black population among the Atlantic provinces and the fifth largest Black population nationally.

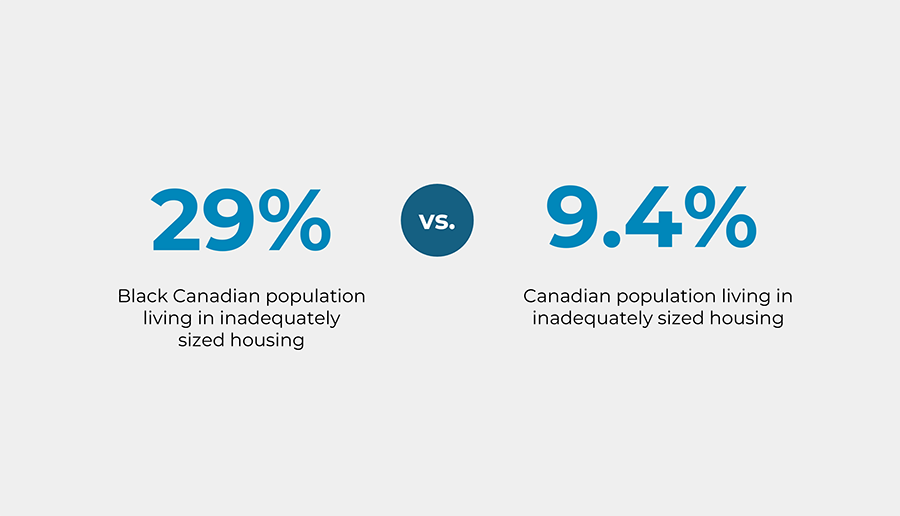

In 2018, according to the Housing in Canada fact sheet dedicated to the Black population, just under a third of the Black population (29%), representing 382,100 Black people, lived in inadequately sized housing. Comparatively, the number of Canadians living in inadequately sized housing was 9.4%.

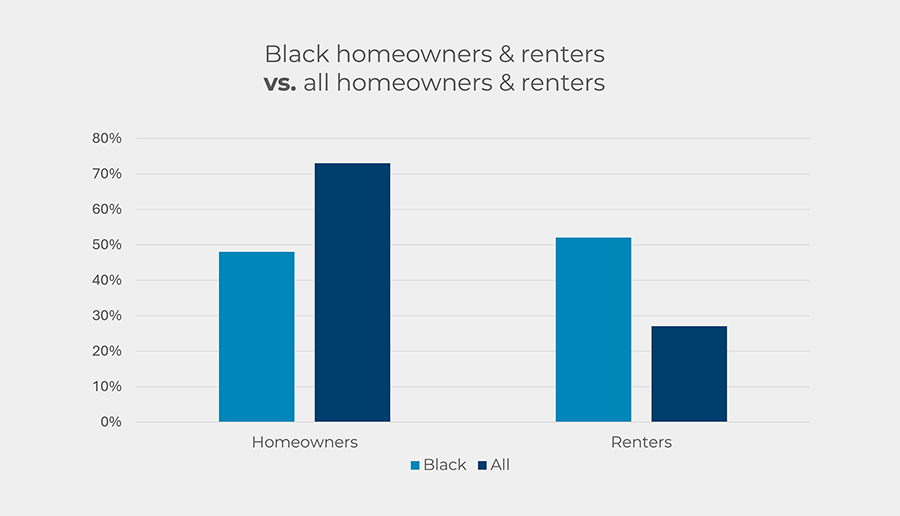

The breakdown between owners and renters in private households is 73% for owners and 27% for renters at the Canadian level. On the other hand, the split for the Black population is 48% owners and 52% renters.

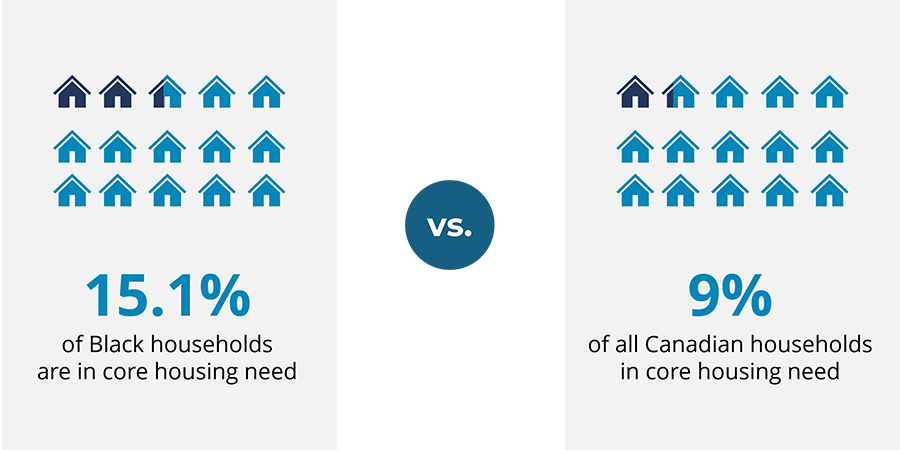

In addition, 15.1% of Black households are in core housing need, compared to 9.0% of the general population. Black people also pay significantly higher rents. The median housing cost paid by Black households was $1,220, while the median housing cost for all Canadian households was $1,050.

In terms of affordability, 19% of Black people living in private households spend more than 30% of their total income on housing.

A range of structural factors, such as higher interest rates, high insurance costs, barriers to home ownership, and even “redlining” in the late 20th century, have added to the complexity of the problem. The term “redlining” refers to the illegal and discriminatory practice of deliberately excluding Black communities from financial services and residential mortgages. The practice originated with loan companies using red markings on maps to demarcate Black neighbourhoods as areas with supposedly low credit risk.

Housing: the cornerstone of social development

The pressure is even greater in the context of the housing crisis. This manifests itself when families from Black communities find themselves forced to reside in deprived areas, often attracting unjustified judgment. While these neighbourhoods may offer relatively affordable housing, the quality of the accommodations leaves much to be desired. Tenants face problems of insalubrity, infestations, and exorbitant energy bills due to inadequate insulation. This vicious cycle leads these families to move frequently, but this extreme relocation creates other problems. Precarious living conditions impact the quality of life and the stability of children, who are constantly on the move, compromising their education and social relationships.

For Neil Armand, the solution is simple: “By focusing attention on the weakest links in the chain, particularly by addressing the specific problems of access to housing for the Black community, we can hope to strengthen the social system as a whole, reduce school drop-out rates and promote a more equitable and sustainable social environment.”

The current situation is even more problematic than in the past, and we need to recognize the structural problems and economic context that are fuelling the housing crisis, contributing to spiralling price rises. It is imperative to adopt a targeted approach and implement specific measures to resolve the structural issues that persist. The Black Community Housing Society wants to create as many mixed-use housing units as possible in Canada. The goal is to have a significant impact on the housing ecosystem in collaboration with all stakeholders in the sector.

The success of individuals from Black communities is no different from that of members of other communities, provided they have access to the same privileges and opportunities,” confirms Armand.

Promising initiatives

In July 2023, the federal government set itself the target of increasing housing projects for Black households through the Affordable Housing Fund (AHF), formerly known as the National Housing Co-Investment Fund (NHCF). The fund aims to increase access to housing financing for Black-led organizations. This kind of initiative is crucial because, in addition to multiplying the housing supply, it encourages the growth and development of organizations led by and serving Black people. However, the fund only sets aside $50 million for these organizations. This is clearly not enough for Black-led community housing organizations to make a real difference.

Provincial governments need to do their part. The Nova Scotia government has recognized this need. It has taken an important step in the fight against historical disparities in its territory by allocating funds for black-led organizations. These funds, accessible through the Community Housing Growth Fund, aim to address the lack of opportunities for Black communities in the housing sector.

Such initiatives have the potential to improve the situation of some of the Black communities in the country. Other Canadian provinces must follow the federal and Nova Scotian example.

Resources for Black-led organizations focused on and serving Black communities

The Centre’s Resource Inventory contains a variety of practical tools for the development and management of community housing. These resources have been developed by various players in the sector. We have compiled a list of resources for Black-led organizations that serve and focus on Black communities for your reference below:

Black-led community land trusts in Canada

Buying while Black: Research project

Foundation for Black Communities (FFBC) Reports

Roadmap for redevelopment plans to confront systemic racism

Programs aimed at supporting Black-led business growth

Accelerator Program – Infrastructure Institute